Tohoku Travel Journal 2025 (1)

The Beginning of the Journey — Fukushima

Awi (Ai)

October 14, 2025, 12:12

This summer, I traveled across the Tohoku region—from August 24 to 29, 2025.

I joined a tour organized by the Hiroshima Peacebuilders Center (HPC).

Hiroshima Peacebuilders Center (HPC)

Study Tour on the Tohoku Reconstruction Process in Japan: Achievements and Remaining Tasks 15 Years after the Disaster

It was a “Study Tour on the Tohoku Reconstruction Process in Japan: Achievements and Remaining Tasks 15 Years after the Disaster.”

I had long wanted to visit Tohoku and learn about the Great East Japan Earthquake.

However, , and planning everything from scratch felt daunting—.

Tohoku was a place I really wanted to see. And above all, this was a tour that automatically came with Professor Shinoda’s commentary. How could I possibly not go?

I was once deeply moved by an article Professor Shinoda wrote on the reconstruction of Hiroshima. That was when I realized that peacebuilding is directly connected to reconstruction.

Japan achieved its postwar reconstruction. Yet the Japanese archipelago remains highly vulnerable to disasters, and no one knows when the next catastrophe may strike. Reconstruction from conflict or war and reconstruction from natural disaster must share many common elements. I believe that is why Professor Shinoda has repeatedly visited Tohoku—and why he planned this study tour.

I wanted to learn about the “remaining challenges.”

I already knew well from his writings that Professor Shinoda analyzes his subjects with cool-headed precision.

And so—with everything aligned—off I went.

August 24, 2025 (Day 1)

From Tokyo Station, I took the Joban Line Limited Express “Hitachi” bound for Fukushima Prefecture.

View of the Pacific Ocean from the Limited Express Hitachi.

I got off at Futaba Station—a brand-new station building

.

The Joban Line suffered devastating damage along parts of the route due to the Great East Japan Earthquake on March 11, 2011. The entire line was finally restored in March 2022.

Along the line, I saw many newly built stations, each displaying evacuation route signs for possible future tsunamis.

As the train approached Futaba, I could see wide fields densely overgrown with vegetation, and occasionally houses—seemingly not very old—left completely unattended. There was no sign of human life.

It was clear—this must be a no-return zone.

Right nearby stands the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, whose impact forced residents to leave.

Futaba Town was entirely evacuated due to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident that accompanied the earthquake and tsunami. While evacuation orders were lifted in some districts on August 30, 2022, media reports in early 2025 still indicated only about 180 residents had returned.

There was a brand-new AEON shopping center near Futaba Station—opened on August 1, 2025, just before our arrival.

We headed for the Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum (Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum).

Futaba was very quiet. The community bus driver told us about the location of Fukushima Daiichi and the damaged buildings along the coast. Through the tall trees, I caught sight of what looked like towers or chimneys of the plant.

We arrived at the museum.

One exhibit that left the deepest impression on me was the diorama of Fukushima Daiichi after the accident.

It was incredibly detailed—the scattered debris from the hydrogen explosions, the distortions and damage of each structure.

Seeing in 3D what I had only encountered through pictures or video added striking realism despite its small scale.

Because I enjoy making things by hand, I couldn’t help but imagine the work required to create such a model. What thoughts did the creators carry as they reproduced the site of a disaster rated Level 7, the highest category on the International Nuclear Event Scale—just like Chernobyl? I cannot know for sure; it is only my speculation.

But I felt that this diorama has a powerful ability to convey the reality of what happened.

The museum also presented, in detail, how TEPCO employees struggled desperately to mitigate the damage amid an unprecedented crisis—while also raising questions about whether the government and TEPCO had been adequately prepared for a major disaster.

Through the timelines and records, it became clear that each person on-site did everything within their power to stop the catastrophe from worsening. Many people fought relentlessly in that confusion to contain the situation.

Before the trip, I had braced myself to see many tsunami videos and learn about painful realities.

Yet from the very beginning, I was confronted with overwhelming devastation and countless emotional stories. My heart felt saturated overflowing with information and emotion.

That night, I could hardly sleep

August 25, 2025 (Day 2)

Our accommodation was not far from the coast, so during free time in the morning, I went to see the sea alone. I love exploring on foot.

Beyond the newly built seawall was the ocean.

The sky was full of clouds, the sun dull and hazy. Something about the scenery unsettled me—the sea, the sky, even the sound of the waves felt frightening. There were stairs leading down the seaside wall, but I couldn’t bring myself to walk all the way to the shoreline.

Even now, I’m not sure why I felt so afraid.

Further along the seawall stood an abandoned triangular-shaped building—the one the bus driver had mentioned.

Painted on the seawall nearby was a warning marking.

A little farther ahead I noticed a red marking as well, so I approached it to check—only to find that beyond this point was off-limits. There were no physical barriers preventing passage, but the seawall clearly ended not far ahead.

Nearly 15 years have passed—yet the nuclear accident is not over.

Later, after returning home, I found a video showing the distance between Futaba and Fukushima Daiichi clearly from above.

In the foreground was the seawall where I had stood.

Just beyond those overgrown trees lay the power plant—undeniably close.

We returned once again to the museum and listened to a storyteller’s session. The themes vary depending on the speaker, but most share first-hand experiences of nuclear evacuation.

The session I attended focused on Futaba’s traditional taiko drums and Bon Odori.

Residents have worked hard to preserve their cultural heritage despite displacement.

By chance—or good fortune—the taiko drums had already been loaded into a truck for a performance the next day, and that same truck helped carry evacuees. Because the drums were with them, the tradition survived. Had the drums been stored at home, they might have been lost forever.

Futaba also has its own unique Bon Odori—music and dance passed down only there.

As residents continued their efforts, they developed connections with Hawaii, where the Futaba Bon Odori is now performed. Bon dances in Hawaii originated from prewar Japanese migrants and have evolved into a major annual event.

The storyteller shared painful experiences of discrimination they faced after evacuation. Hearing that, I realized that Futaba’s Bon Odori must be a vital anchor of identity—a thread connecting residents scattered far from home.

When people are placed in unfamiliar cultural surroundings, their sense of identity becomes even more important. Preserving that identity is surely a core element of reconstruction.

After all—without residents striving to reclaim their home, there can be no true “reconstruction.”

We boarded the Limited Express Hitachi again, heading north toward Miyagi.

There was so much to think about.

Gazing out the window, I tried to organize the thoughts welling up inside me.

Travel companion: Bamse.

(Continued in Part ②)

Tohoku Travel Journal 2025 (2)

Miyagi

Awi (Ai)

October 27, 2025, 21:07

Continued from Part ①.

August 25, 2025 (Day 2)

From Fukushima we headed to Miyagi, passing through Sendai and changing trains for Ishinomaki.

I gazed out the train window at the overcast, white sky. Suddenly I noticed several planes flying in formation—four of them, if I recall correctly—streaming white smoke in perfect alignment.

Blue Impulse!

It occurred to me that the JASDF Matsushima Air Base is nearby—and Blue Impulse is based there. By the time I realized it, the aircraft had traced a graceful curve and vanished into the pale clouds. No chance to snap a photo, of course.

The Matsushima base also suffered devastating damage in the Great East Japan Earthquake, but most Blue Impulse aircraft happened to be away from the base and escaped harm. I knew they had become one of the symbols of recovery, so even catching a glimpse of them here in Tohoku, however briefly, made me happy.

We arrived in Ishinomaki and headed for the Okawa Elementary School Earthquake Ruins.

https://www.ishinomakiikou.net/

When the Great East Japan Earthquake struck, the tsunami surged upriver from the sea. The embankment along the Kitakami River—running right beside Okawa Elementary—collapsed, causing catastrophic damage in the area. Evacuation at the school was delayed; 84 students and staff lost their lives or went missing.

On the way there, we drove along the Kitakami River in a taxi. It was my first time seeing it—a vast river brimming with water.

In the photo, the area at the lower left is where Okawa Elementary stood. We followed the left bank to reach the site.

Before and after the disaster — Okawa Earthquake Memorial Museum

As we approached the school site, I noticed the buildings stood on ground lower than the bridge and the road along the embankment. From the schoolyard, you could see only the embankment itself—nothing of the river beyond.

Topographic model — Okawa Earthquake Memorial Museum

You can see that a hill rises immediately behind the school, on the side opposite the Kitakami River.

But looking at the hill from the school grounds, the slope was faced with concrete up to higher than an adult’s height, and there were no stairs. The incline was steep; I thought it would be very hard for a small child to climb that wall unaided.

Why was this site judged suitable for an elementary school in the first place?

I had no words when I stood there, and even now, writing this, the feeling remains. There are so many whys and hows that I don’t think should ever fade from my mind.

August 26, 2025 (Day 3)

We visited the Ishinomaki Minamihama Tsunami Memorial Park.

https://www.city.ishinomaki.lg.jp/cont/10353300/kurashi/kurashi/1027578.html

A broad swath of the Minamihama coastal district, devastated by the tsunami, has been developed into a memorial park. It is vast. I walked from the “Ganbarō Ishinomaki” sign, which stands slightly left of center, toward the “1-Chōme Hill” area to the right.

The “Ganbarō Ishinomaki” sign, with sunflowers behind it.

It was late summer, and many of the blossoms were heavy with seeds and hanging their heads. Sunflowers are well known as a symbol of recovery.

Within the park is the Miyagi 3.11 Tsunami Disaster Recovery Memorial Museum.

https://www.pref.miyagi.jp/site/densyokan/

As its name suggests, the exhibits focus on the tsunami.

From the Miyagi Prefectural Government website

I learned that the height of the museum building matches the height of the tsunami that reached Minamihama—so it is designed as a reminder never to forget.

After visiting the museum, I climbed to 1-Chōme Hill. The view today is entirely different from the pre-disaster landscape that was once a residential neighborhood.

On the lawn, small robotic mowers buzzed quietly back and forth. The park felt very peaceful.

From Ishinomaki we took the train to Onagawa, the terminus of the Ishinomaki Line.

Suddenly, it felt like we’d arrived somewhere stylish.

There’s a hot spring facility inside the station building, and a free footbath out front.

The area around the station has been redeveloped as a roadside station (Michi-no-Eki) with a refined, modern atmosphere.

Facility guide (Seapalpia Onagawa): https://onagawa-mirai.jp/

Michi-no-Eki official site: https://www.michi-no-eki.jp/

From the Michi-no-Eki website

A straight road runs from the station down to the sea. Because Onagawa’s seaside districts were devastated by the tsunami, nearly all the buildings around the station are new. Even on a weekday there were quite a few visitors; I imagine it’s much livelier on weekends.

We stopped by the Onagawa Tourist Information Center “Platto” and listened to a guide speak about the disaster and the town’s reconstruction.

https://www.onagawa.org/

A distinctive feature of Onagawa’s recovery is that the town did not build a massive seawall. Accepting that perfect disaster prevention has limits, they adopted a disaster mitigation approach to urban planning.

From the Onagawa Tourism Association website

Onagawa has little flat land; the terrain slopes down toward the sea. The lowest zone, at 1.9 m, is reserved for parks and fishing port facilities. The next tier, 5.4 m, serves as a commercial–industrial zone that also functions as a protective barrier. Residential areas and public facilities are placed on elevated ground over 20 m.

We then visited the Old Onagawa Police Box Ruins, just across the national road on the seaward side from the roadside station.

The police box lies on its side, apparently overturned by the force of the receding tsunami.

You look down on the ruin from above—because the surrounding area was raised with fill during reconstruction.

Vegetation now grows wild around it. I was told this is deliberate policy in Onagawa: they won’t intervene unless overgrowth poses a hazard, choosing not to spend heavily given a future of population decline and aging.

Onagawa is famous for Pacific saury (sanma). It was delicious.

From Onagawa we headed back toward Ishinomaki and continued north along the Kesennuma Line BRT. Because the JR East Kesennuma Line and Ōfunato Line suffered catastrophic tsunami damage, the former rail corridors now serve as dedicated busways. The BRT doesn’t just follow the old tracks; it also detours to places like hospitals and government offices, making good use of bus mobility.

JR East — Kesennuma Line BRT / Ōfunato Line BRT (Bus Rapid Transit)

From the JR East website

Our next destination was Shizugawa (Minamisanriku Town), where we visited the Minamisanriku 3.11 Memorial Park.

https://www.m-kankou.jp/spot/17731.html

Here stands the ruin of the Minamisanriku Town Disaster Prevention Government Building—only its steel frame remains.

The twisted steel is haunting. The frame wasn’t stripped down after the fact; this is how it stood once the waters receded. The ferocity of the tsunami is palpable.

We walked past the ruin and climbed a hill within the park. Beyond the seawall, the ocean came into view.

Adjacent to the park is the roadside station “Sansan Minamisanriku.”

https://www.michi-no-eki.jp/

Most shops happened to be closed that day, unfortunately.

If you continue toward the sea from the roadside station, you’ll find a moai statue. Since we were there, we went to see it.

This article explains clearly why there is a moai statue here:

https://www.m-kankou.jp/feature/20334.html

August 27, 2025 (Day 4)

We started under threatening skies. Still, I’d seen notices everywhere saying Miyagi had been dry for a long stretch, so the rain was much needed.

We visited the Kesennuma City Great East Japan Earthquake Memorial Museum, touring the ruins of the former Kesennuma Koyo High School with a guide. The memorial museum is built into the ruined school building; the two are connected side by side.

From this angle, it almost looks like an ordinary school.

But—

Between the wings of the building lay all kinds of debris.

I learned that the massive damage to the fourth-floor wall was caused when a refrigerated factory, swept away by the tsunami, slammed into the building.

Inside the school.

At the time of the disaster, the students who were on campus followed their teachers’ instructions and immediately evacuated to higher ground; all of them survived. The principal decided that staff would remain in the building to move students’ important records to the upper floors; both the staff and the records made it through safely.

I heard that many citizens supported turning Koyo High School into a disaster memorial site. I found myself thinking how much hope it must have given the local community that every student survived, even amid such devastation.

From the roof of the ruin you can see it clearly: the open area next to the museum is now used as a putting golf course.

They charge fees to users of the course, and the museum has steady attendance—part of an effort not to rely solely on tax revenues for upkeep.Our last stop in Kesennuma was the Kesennuma City Reconstruction Memorial Park.

Set on a small rise, it offers a fine view of the sea. The parking lot is well maintained and accessible by car, but the route includes some narrow, confusing lanes. There are stairs from the foot of the hill as well. Climbing all the way up is good exercise—though it might be quite tough for older visitors.

Looking at the steep slope, I caught myself thinking maintaining this is going to be hard… it’s not like you can turn it into a putting course.

Before I knew it, that’s where my mind went whenever I saw a new facility.

Even within the same prefecture of Miyagi, each municipality’s approach to “disaster heritage”—how to present it, how to conserve it, and how to keep facilities running—differs markedly. Do you charge admission or make it free? Do you preserve ruins or not? Who will handle maintenance, and how? How do you reduce the burden on the future?

After a great catastrophe, communities face fork after unexpected fork, forced to choose paths they had never imagined. And along any path, it’s still too soon to say whether the choices were “right.”

I am gradually coming to understand the “remaining challenges” of reconstruction.

(To be continued in Part ③.)

Tohoku Travel Journal 2025 (3)

Iwate

Awi (Ai)

October 29, 2025, 22:20

Continued from Part ②.

August 28, 2025 (Day 4)

We boarded the BRT in Kesennuma again and continued on to Iwate.

Our first stop was Roadside Station Takata Matsubara in Rikuzentakata—there’s a BRT stop right there.

Roadside Station Takata Matsubara

https://takata-matsubara.com/

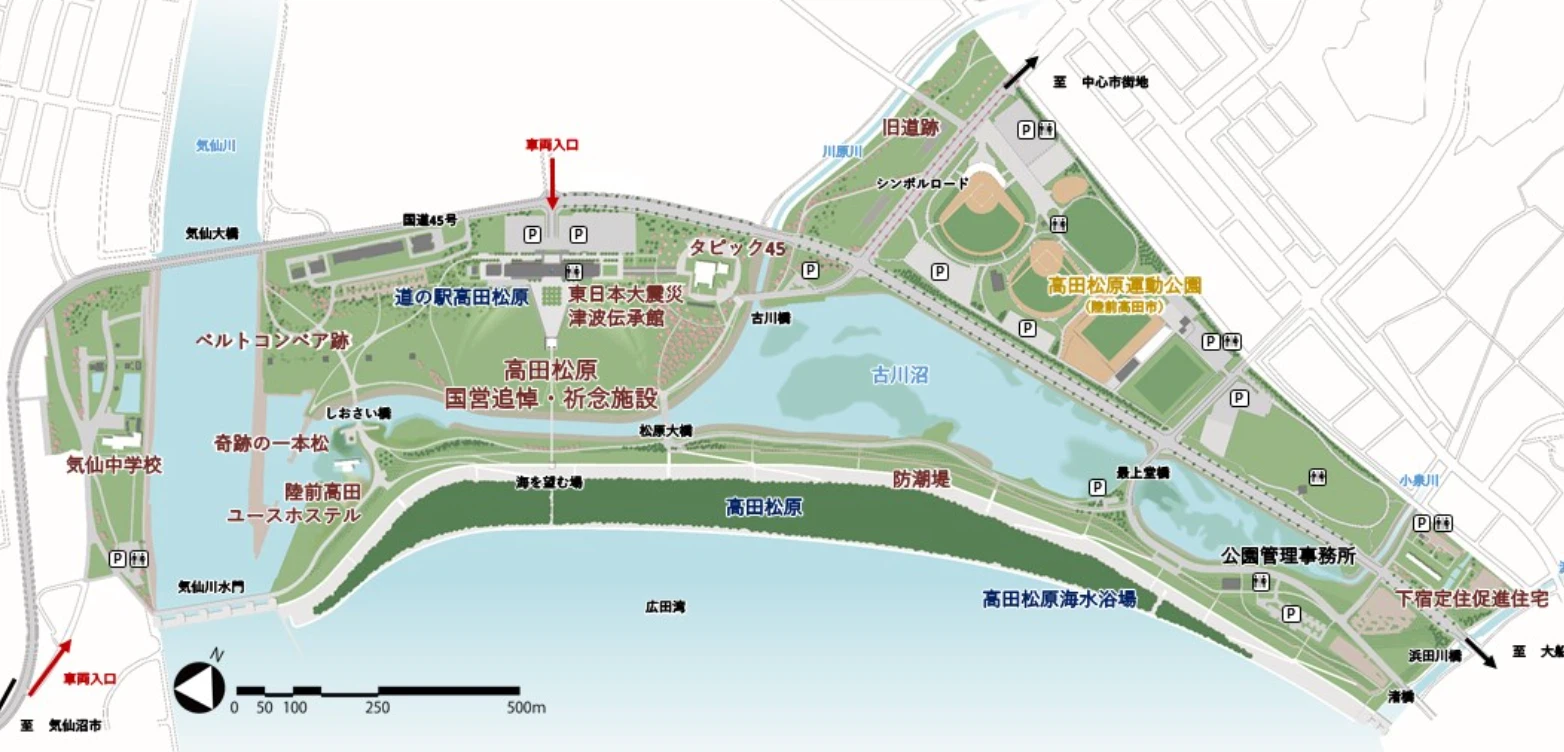

The roadside station sits close to the coast, adjacent to the Iwate Tsunami Memorial—The Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami Memorial Museum. The surrounding area has been developed as a memorial park, and you can walk from there to several earthquake ruins.

Takata Matsubara Tsunami Reconstruction Memorial Park

https://iwate-fukkokinen-park.jp/

Looking at the map, it’s probably more accurate to say that the roadside station, the memorial museum, the preserved ruins, and the Takata Matsubara beach are all contained within the vast grounds of the Reconstruction Memorial Park. (It’s hard to describe clearly; I hope my clumsy explanation doesn’t come off as disrespectful to locals!)

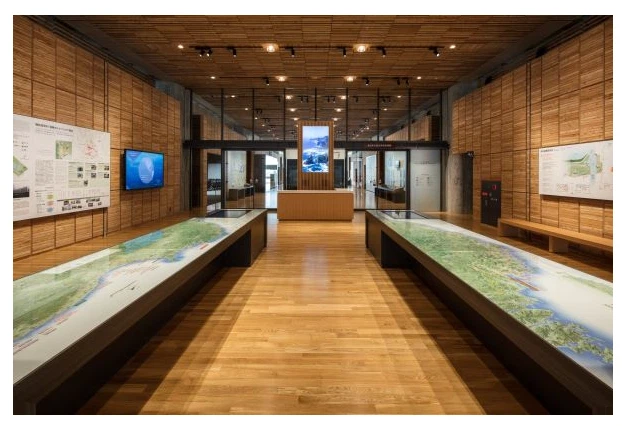

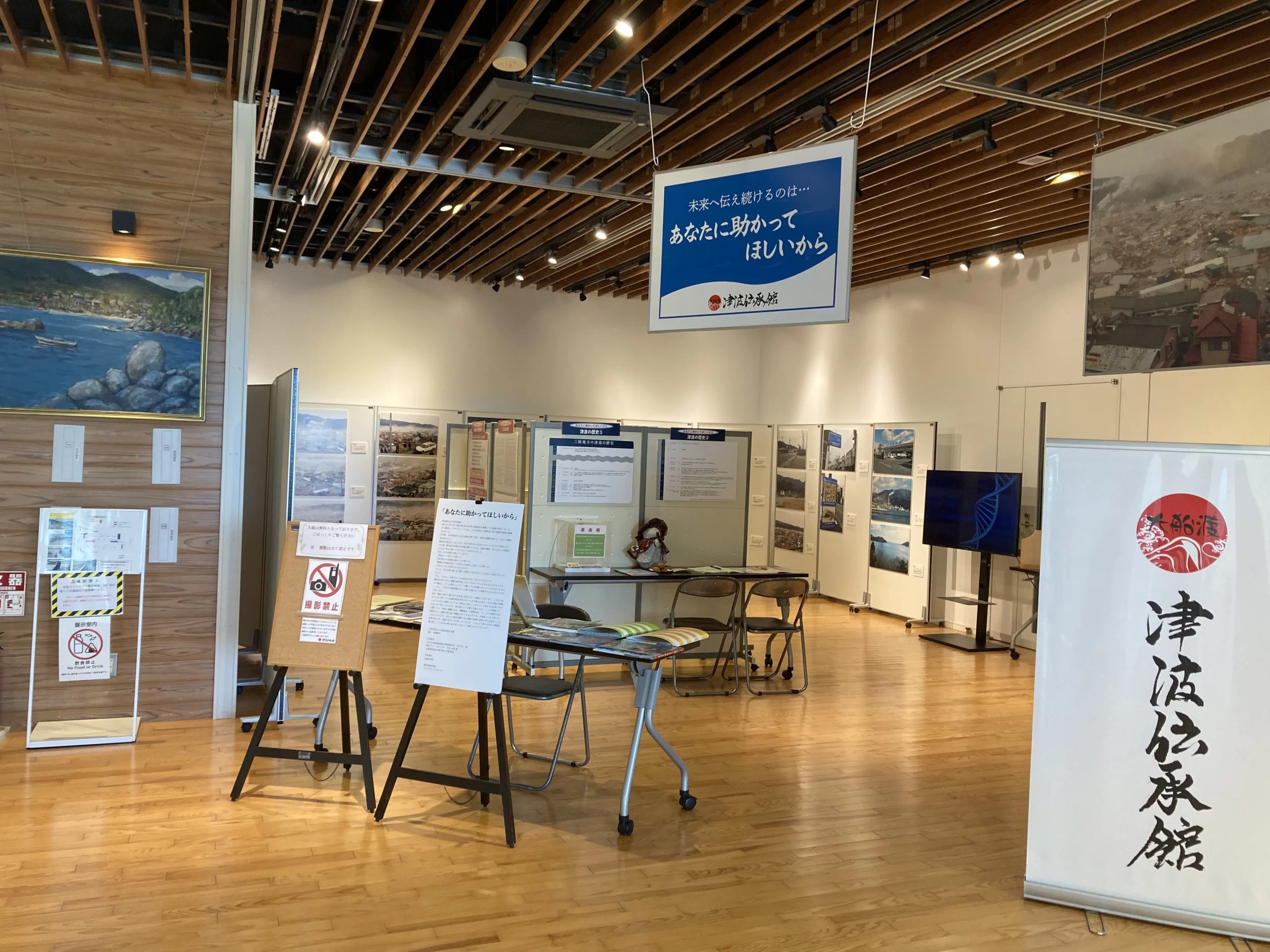

First, we visited the Iwate Tsunami Memorial (Iwate TSUNAMI Memorial).

Iwate TSUNAMI Memorial

The map at the entrance is overwhelming.

From the Iwate TSUNAMI Memorial website

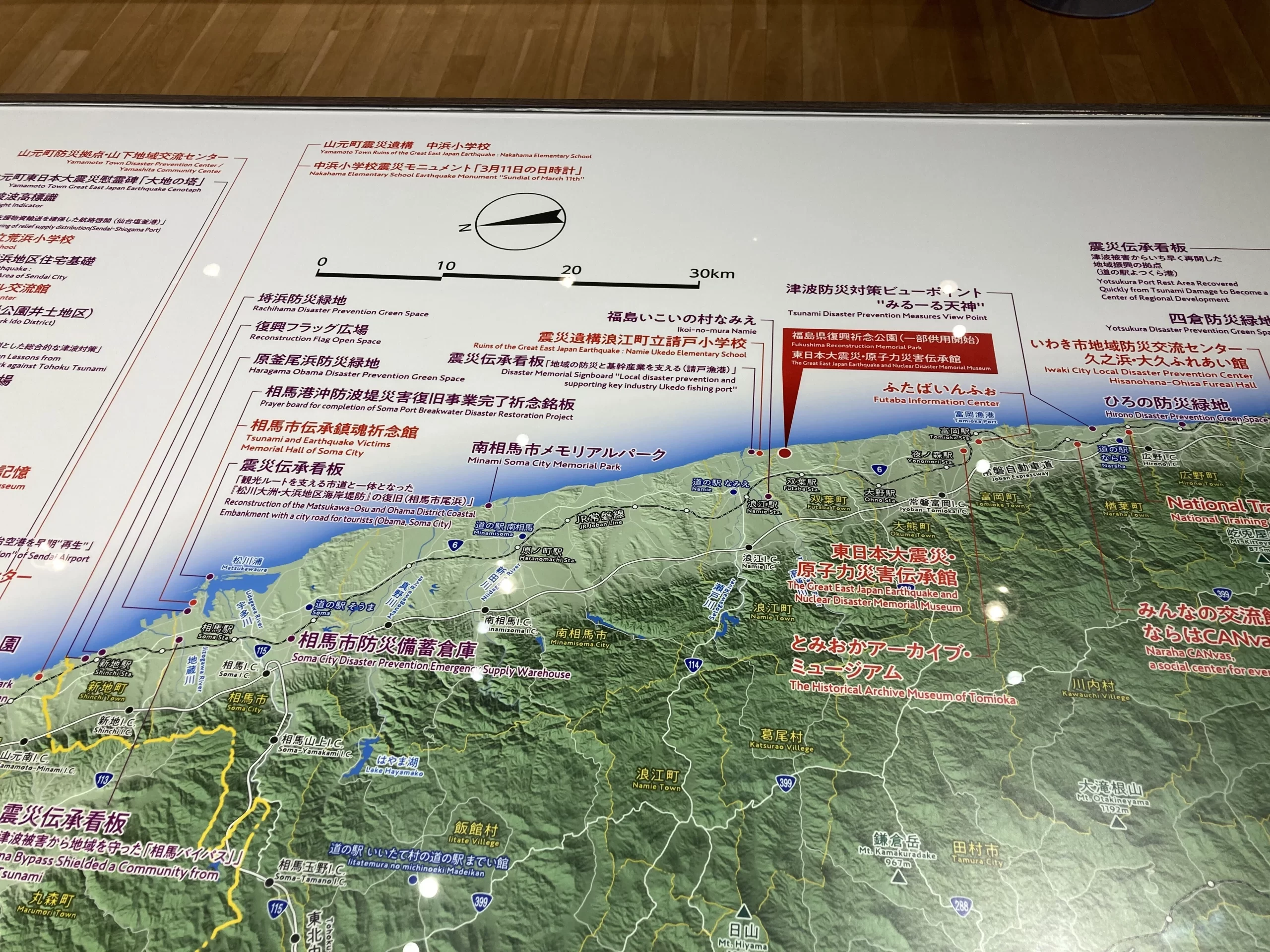

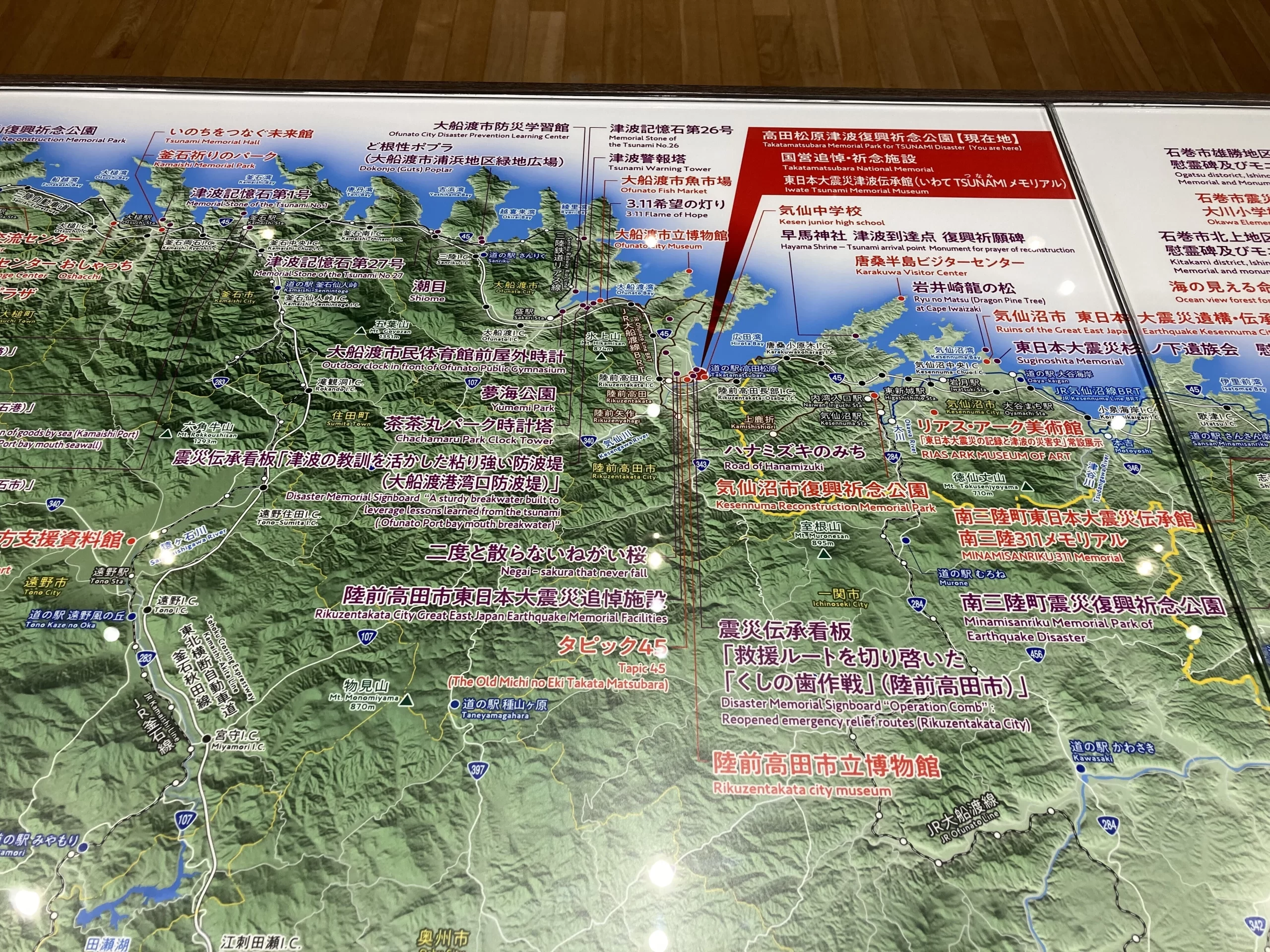

The coastline of Fukushima.

The coastline of Miyagi.

And the Sanriku coast—where we are now.

We really have been traveling this shoreline all along…

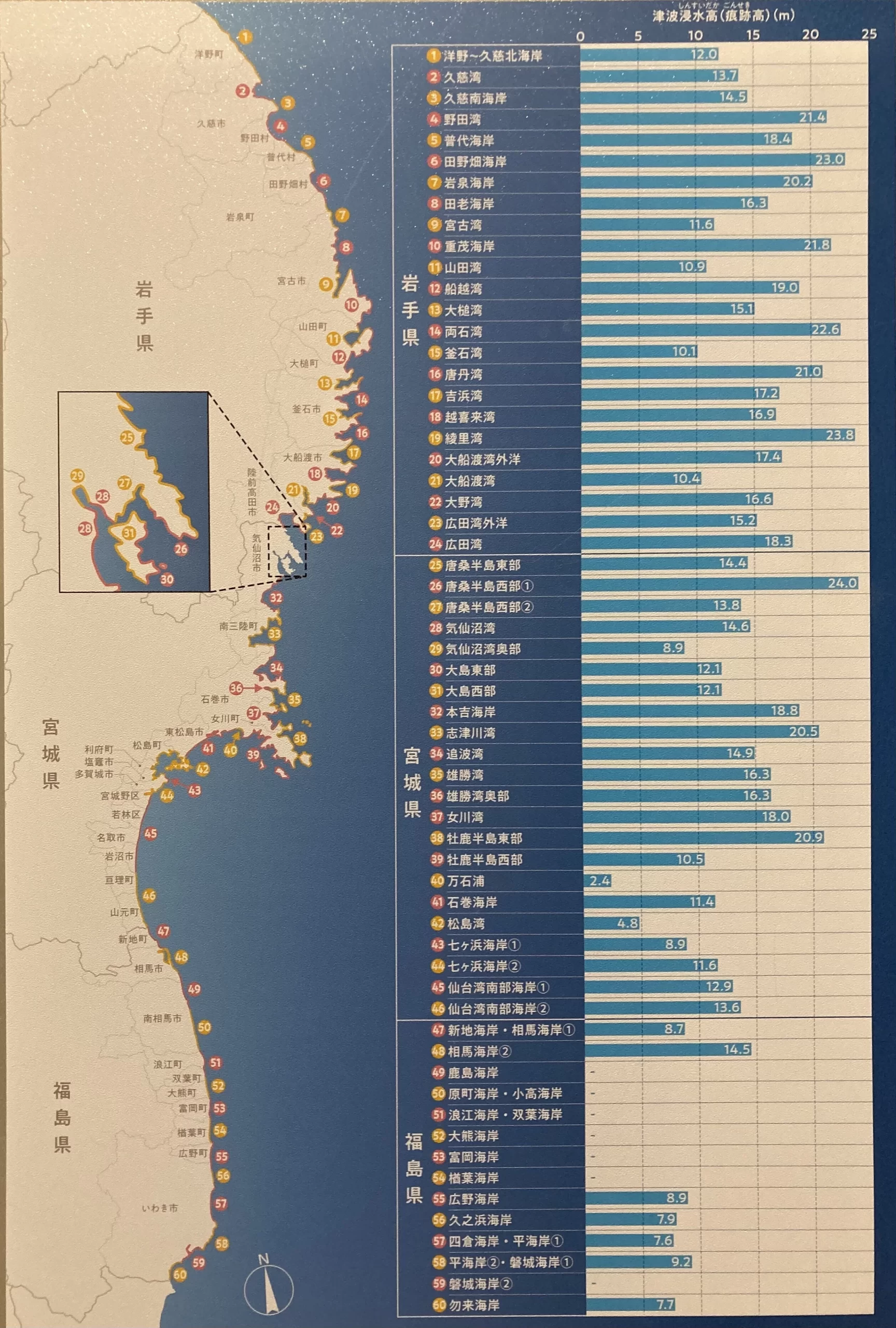

The exhibit showing tsunami inundation heights in each area is arranged side by side across the three prefectures, making comparisons very clear. You can see how devastating the damage was along the deeply indented rias coast of Sanriku.

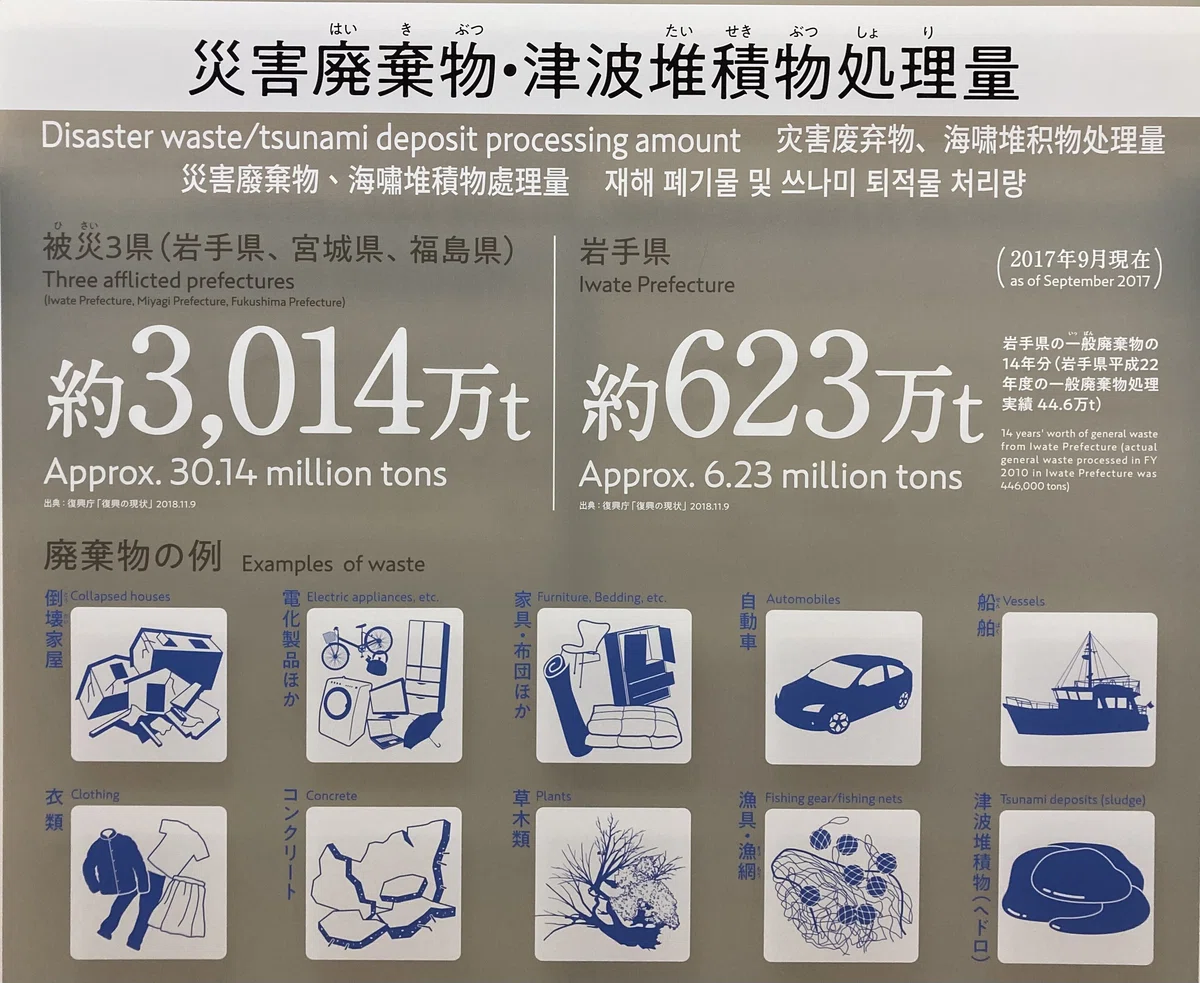

The volume of disaster waste and tsunami sediment processed—numbers so large I can hardly fathom them.

Leaving the museum, we set out to walk through the Takata Matsubara Tsunami Reconstruction Memorial Park and visit the disaster ruins.

From the flower altar, we looked out toward the sea.

We could see many young pine trees being cultivated. The shore was close, so we went down to it and watched the calm surf and quiet sea.

We continued on to the ruins: the Rikuzentakata Youth Hostel.

And then, the “Miracle Pine.”

On this coastline, devastated by the tsunami, a single pine tree remained standing and came to be known as the Miracle Pine. It withered the following year, but to preserve it as a symbol of recovery, it was carefully conserved and is now installed as a monument in its original location.

Across the shore, not only are new pine saplings being raised, but mature pines have been planted as well, and pinecones lay scattered here and there. It became clear to me that restoring the vista of a vast pine forest along this beach is a vital part of the region’s reconstruction. The beautiful Takata Matsubara shoreline must be a deeply cherished place for the people who live here.

August 29, 2025 (Day 5)

That day we visited the Ōfunato Tsunami Museum in Ōfunato City, toured the facility, and listened to a talk by someone who had experienced the tsunami firsthand.

Ōfunato Tsunami Museum

Our speaker was a former executive of a local Japanese confectionery shop who now dedicates himself to serving as a tsunami storyteller. He had filmed continuously from the moment the earthquake struck and showed us an edited record. As soon as the violent shaking eased, he made a complete circuit of the company grounds, calling on employees to evacuate; everyone moved to high ground and survived. The shop had conducted regular evacuation drills long before the 2011 disaster.

I had heard of Iwate’s “tsunami tendenko” ethos. When I asked what mindset locals had before the disaster, he said he had remembered a childhood tsunami and was convinced another would come someday, so he constantly stressed the importance of evacuation to his staff. If I recall correctly, the confectionery building was three stories tall, yet the water rose above the roof; the entire structure was submerged. Had anyone stayed behind at the shop, they likely would not have survived.

“What does tsunami tendenko mean?” (Weathernews)

He also spoke about normalcy bias. In the many videos made by him and others locally, he noticed numerous instances of people acting strangely—driving toward the sea even as the tsunami approached, or strolling outside unhurriedly with the waves almost upon them. He didn’t know what became of them afterward; thinking about it sent a chill down my spine.

What struck me most was his point about making an evacuation pact within the family—agree in advance that if something happens, each person will evacuate immediately to safety, and when the time comes, trust that your loved ones have already done so.

He said many people died because they tried to return home from elsewhere, worried about whether their families had evacuated. Love for family, when it turns into fear, can rob us of sound judgment. If a disaster strikes when family members are in different places, believing that they will evacuate and be safe can help you stay calm and protect yourself first—which in turn reduces casualties. Trusting that your loved ones are safe is also a way of protecting your own life; conversely, for your family’s sake, everyone must choose the course that protects their own life first when disaster strikes. It sounds obvious, but for me it was a blind spot.

We also visited the Memorial Wall of Names honoring the victims of the Great East Japan Earthquake in Minato Park, along with other monuments.

Then we headed north on the Sanriku Railway Rias Line.

The Sanriku trains are simply adorable.

Scenes from the stations—sea and sky, and long stairs descending from the platforms.

We could see the long, long seawalls, too.

I watched the ocean views the whole time with Bamse by my side.

Next we went to Kamaishi City, visiting Unosumai Tomosu in Unosumai.

Unosumai・Tomosu (official site)

This is another integrated complex of facilities related to the disaster.

Kamaishi Memorial Park, with its cenotaph.

All around it stand new houses and buildings.

The names of those who lost their lives are inscribed on the monument. I have seen such lists at several memorial parks along the way, and each time I found myself afraid to look directly at every name. So many people truly died. The victims are not mere numbers; they were individuals, with names, living their lives in these communities. Confronted with that reality, I felt a swirl of unspeakable emotion again and again.

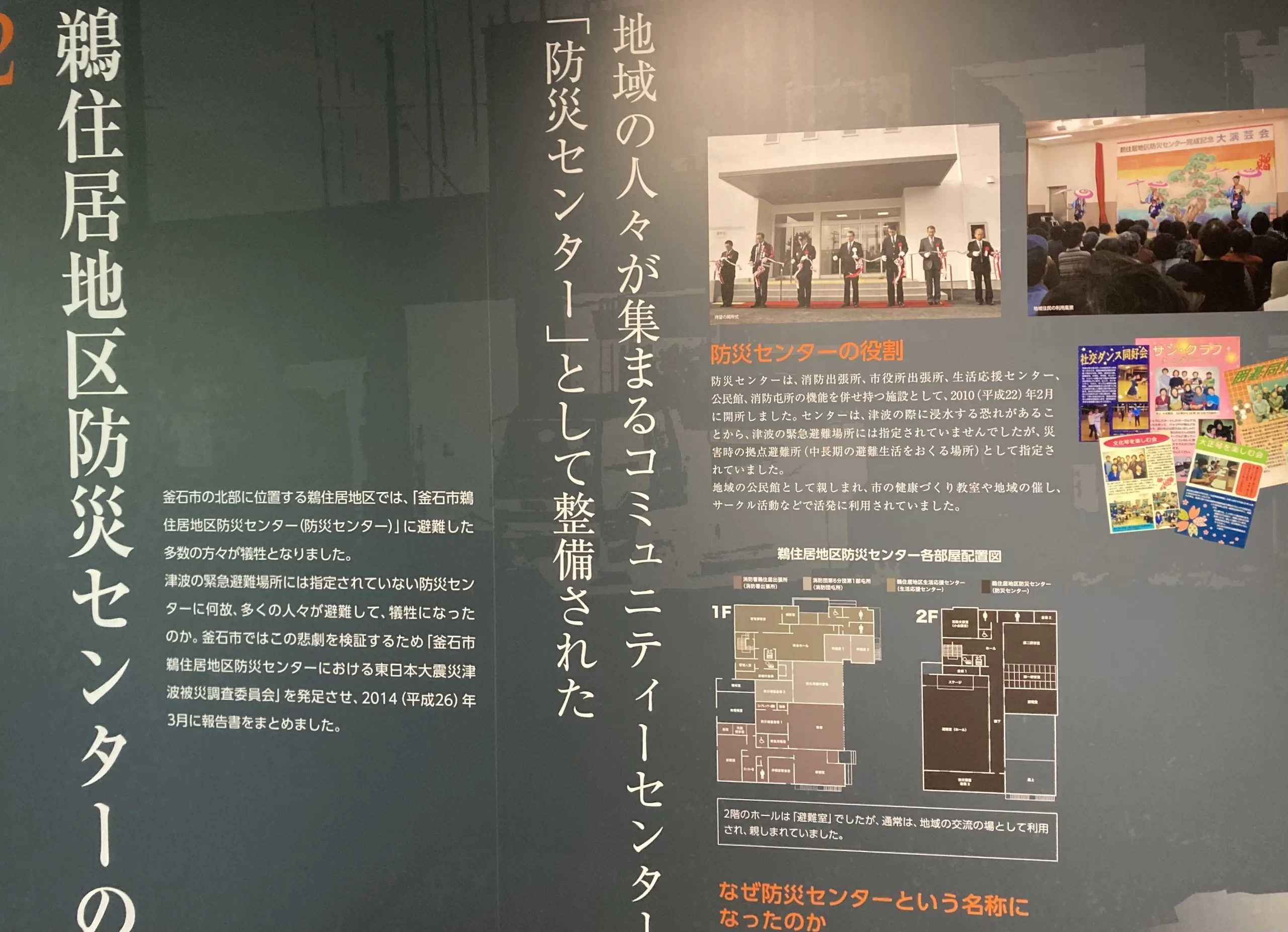

Next door is the Inochi o Tsunagu Mirai-kan (“Museum for Connecting Lives to the Future”). In the Unosumai district, many people who evacuated to the Disaster Prevention Center lost their lives.

The center stood on low ground and was designated not as a tsunami emergency evacuation site but as a facility for medium- to long-term shelter during disasters. It also served as a well-loved community center. Post-disaster reviews suggest that the name “Disaster Prevention Center” likely led to the mistaken belief that it was a safe evacuation site in a tsunami, drawing many people there and contributing to the heavy loss of life.

The tsunami is said to have reached the level of the second-floor ceiling. More than 160 people died there. The surrounding devastation was so severe that rescue operations at the center did not begin until the third day after the disaster. Even the roughly thirty people who survived endured unimaginable fear and anxiety.

I had heard similar stories in Miyagi—people who evacuated because a tsunami was coming but did not go to higher ground and thus did not survive. Again and again I encountered the word “beyond expectations”—as in, no one had imagined the water would ever come this far, because it never had before.

Traveling steadily north from Fukushima, I came to understand how perceptions differed from place to place, even within the same disaster—and how those differences stemmed from the causes of evacuation. In Fukushima, many people had no tsunami damage yet could not return home for a long time because of the nuclear accident; the focus there is on the plant and radioactive contamination. In Miyagi, the focus is on the vast destruction wrought by the tsunami; in Iwate, too, the tsunami’s devastation is central—but there is also the distinctive theme that the tsunami tendenko ethos helped save many lives. That is how it felt to me.

We boarded the Sanriku Railway again and headed for Miyako City.

Late summer.

We arrived in Miyako, where the group portion of the tour came to an end.

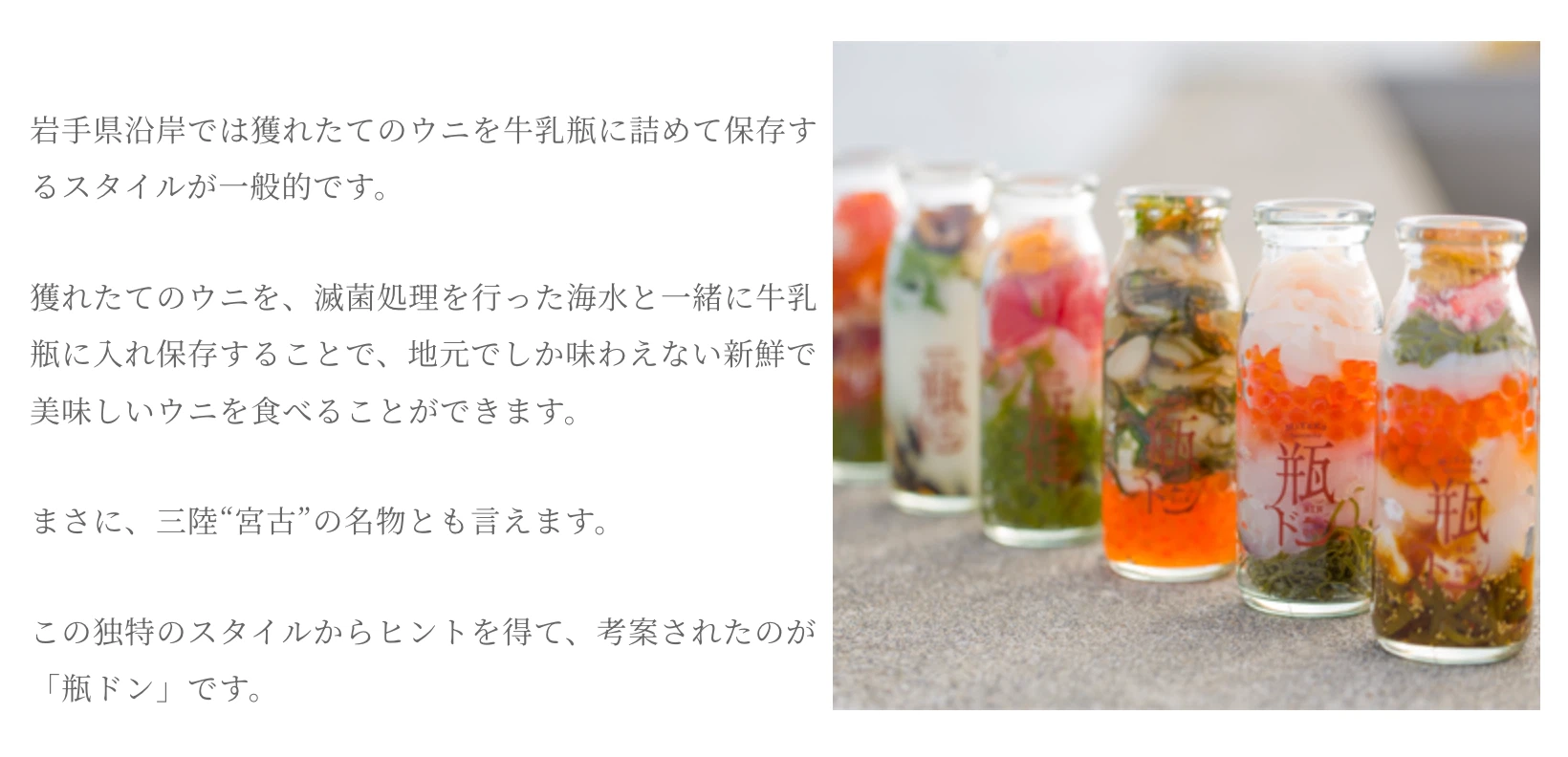

That evening, at our farewell gathering, we enjoyed bin-don, a local Miyako specialty.

“Let’s Try Bin-don” — Miyako Tourism and Culture Association

https://kankou385.jp/eat/bindon/

Every kind of seafood I had in Tohoku was delicious. The Sanriku wakame was wonderful too—I love wakame, so I ate a lot of it (it was served at every hotel breakfast).

As for sake, I especially liked the crisp, clean flavors of Suminoe from Ishinomaki’s Suminoe Sake Brewery. The seafood ramen in Kesennuma had a rich, savory broth—so good.

I ate so well I came home a little heavier.

It was a journey filled with many painful sights, and yet Professor Shinoda was always warm while maintaining a fitting sense of decorum. He spoke candidly about his own views, occasionally lacing them with his trademark humor, and we participants enjoyed gentle cross-cultural exchanges with one another. I realized how much joy there is in learning what I didn’t know—and in having my intellectual curiosity satisfied.

There was much to ponder, but I wasn’t sunk in contemplation the whole time. I remember laughing a lot.

When I look back on this trip, the first feeling that rises up is simply: I had a wonderful time.

I’m truly glad I was able to meet Professor Shinoda, talk with him, and travel through Tohoku.

To be continued in Part ④.

フォームの始まり

Tohoku Travel Journal 2025 (4)

Journey’s End

Awi (Ai)

October 31, 2025, 08:28

August 28, 2025 (Final Day)

The last day was free time.

I’d heard from Professor Shinoda that he hadn’t yet traveled north from Miyako, so I thought, “Maybe I’ll do a little scouting?” and decided to take a solo trip to Taro, a small fishing town north of Miyako. It had been a while since I’d gone alone to a place I didn’t know. I felt a little nervous—and a little excited.

Taro also has disaster ruins and a brand-new memorial museum that opened this June.

I headed north from Miyako on the Sanriku Railway.

Wait—this train looks unfamiliar…

I asked the conductor to be sure. On local lines with few departures, one wrong train can be a big problem.

He said the train was donated by Kuwait. I was on the right one.

The interior was surprisingly stylish and luxurious.

A four-seat bay with a table—all for me and Bamse. Quite a luxury.

I got off at Shin-Taro Station, a small, unstaffed stop.

I didn’t have much time. The farther you go into the countryside, the fewer trains there are, and connections don’t line up neatly. Miss one train and the next might be an hour and a half later; midday services are even sparser, which means longer waits on transfers. Counting backward from my return time, the only option was to walk quickly and make the train I’d planned.

Guided by a map app, I headed straight from the station toward the sea. Once you spot the massive seawall, you know which way to go.

From atop the seawall: facing the ocean and looking to the right, the long, high wall runs all the way to the base of the mountain.

To the left—again, an unbroken seawall.

Beyond the seawall, the sea.

A great floodgate.

So this is what they close when a tsunami comes.

A wall rising from the sea.

I’ve heard the seawall’s designed lifespan is fifty years. Fifty years from now, will this country be able to build such a long, colossal seawall again? Or will there be new technology that makes seawalls cheaper?

I walked along wondering about that. The fishing port at Taro was calm.

I crossed the port to the Taro Kanko Hotel Ruins. You can see clearly how high the tsunami reached.

Over the course of this journey I’ve learned what to look for. Even at a quick pace, I think I managed to capture the key points in photos.

As I walked, I saw a marker showing the tsunami inundation depth. I truly saw many of these signs throughout Tohoku.

I held my arm up as high as I could to take this picture. It means that if I had been standing here at that time, I would have been beneath the waves.

I visited the Miyako City Disaster Archives and Remembrance Museum.

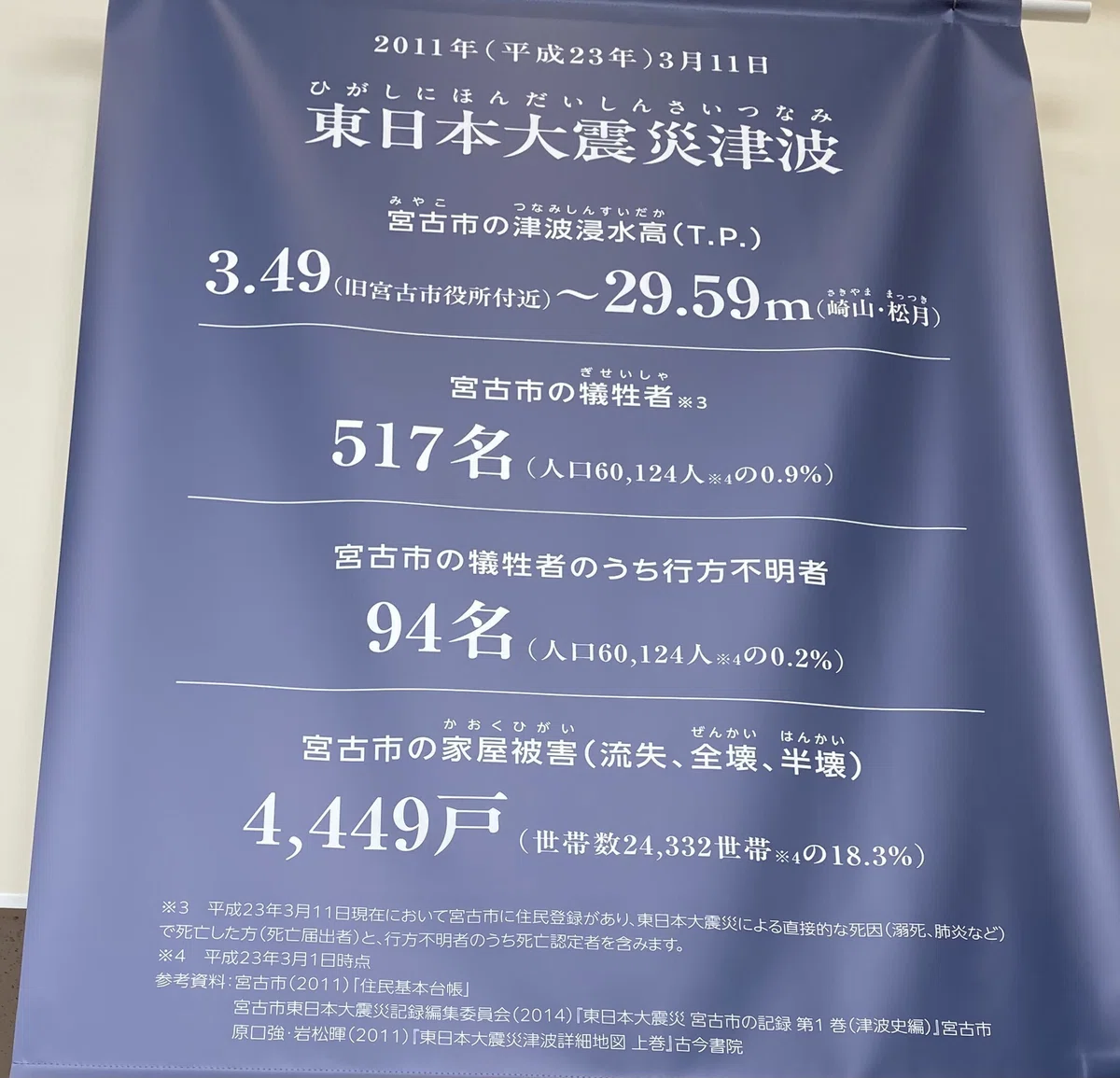

In front of the museum was this display:

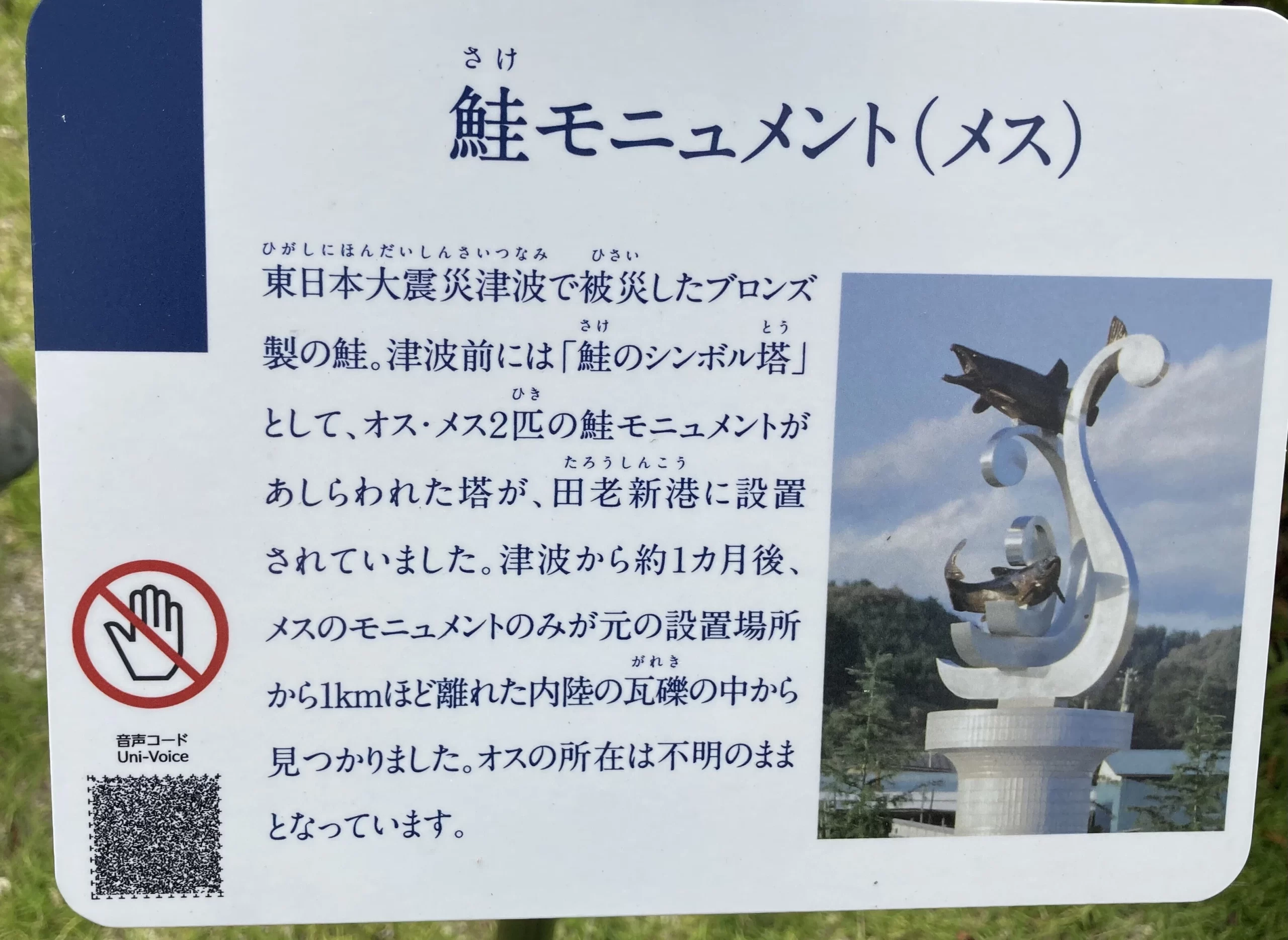

A salmon monument—scarred and battered.

So many people lost someone dear to them in the disaster. I felt this monument embodied that grief.

Today the sea that stole so much was a beautiful, tranquil blue, as if nothing had happened. More than fourteen years have passed since that day, and here lay this salmon, resting quietly on the grass. I wondered where it had been, and how, until it came to this spot. The black tsunami and the blue sea look utterly different, and yet they are the same thing. I didn’t know then—and still don’t—how to make peace with that in my heart.

The museum itself is modest. Only the minimum number of staff were on duty in the office. Most of the exhibits were printed on fabric rather than fixed panels—easy to change out. The materials were organized by area; there were testimonies from those who worked on the disaster sites and videos of survivors’ accounts, all set up for visitors to browse freely.

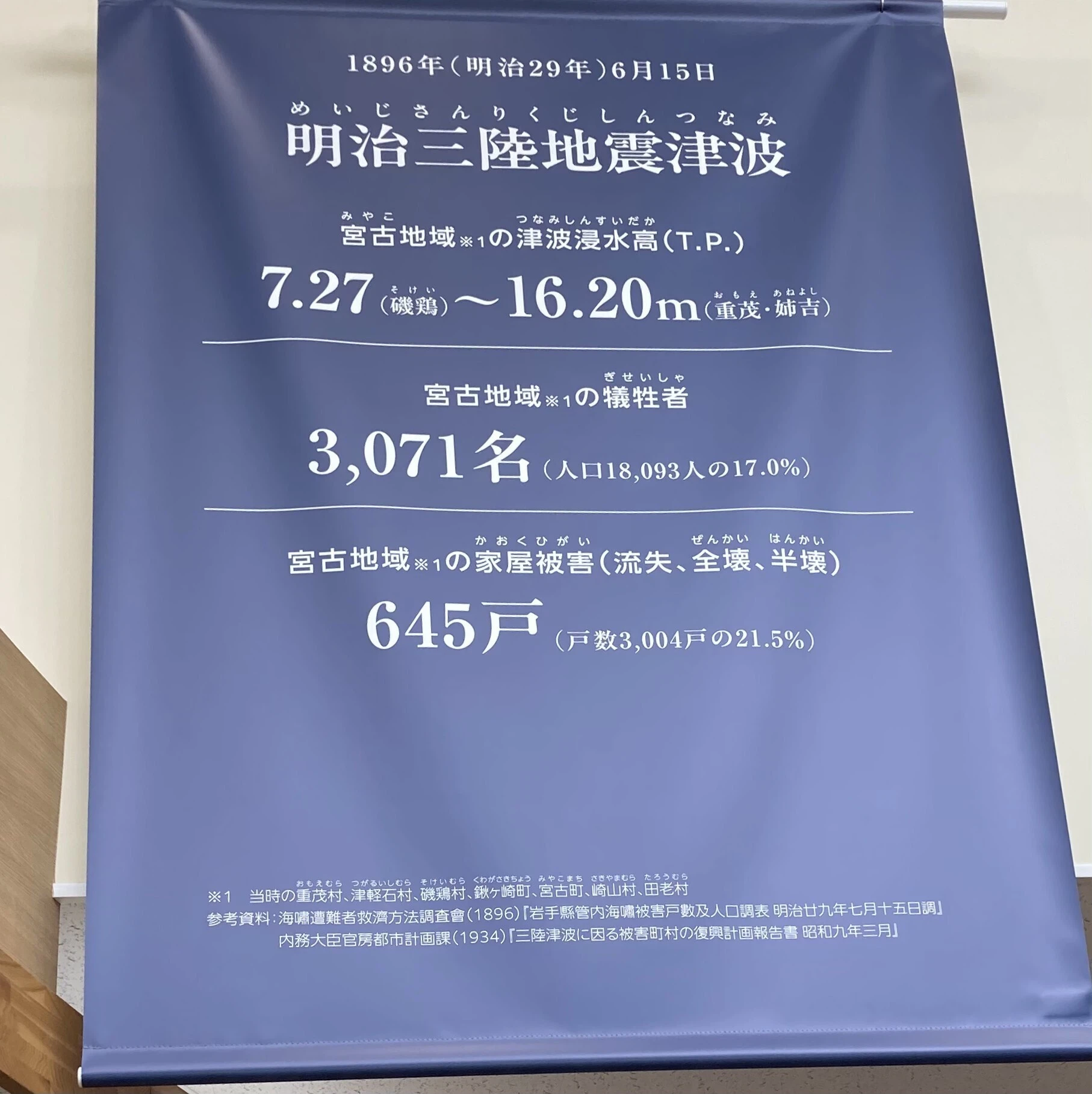

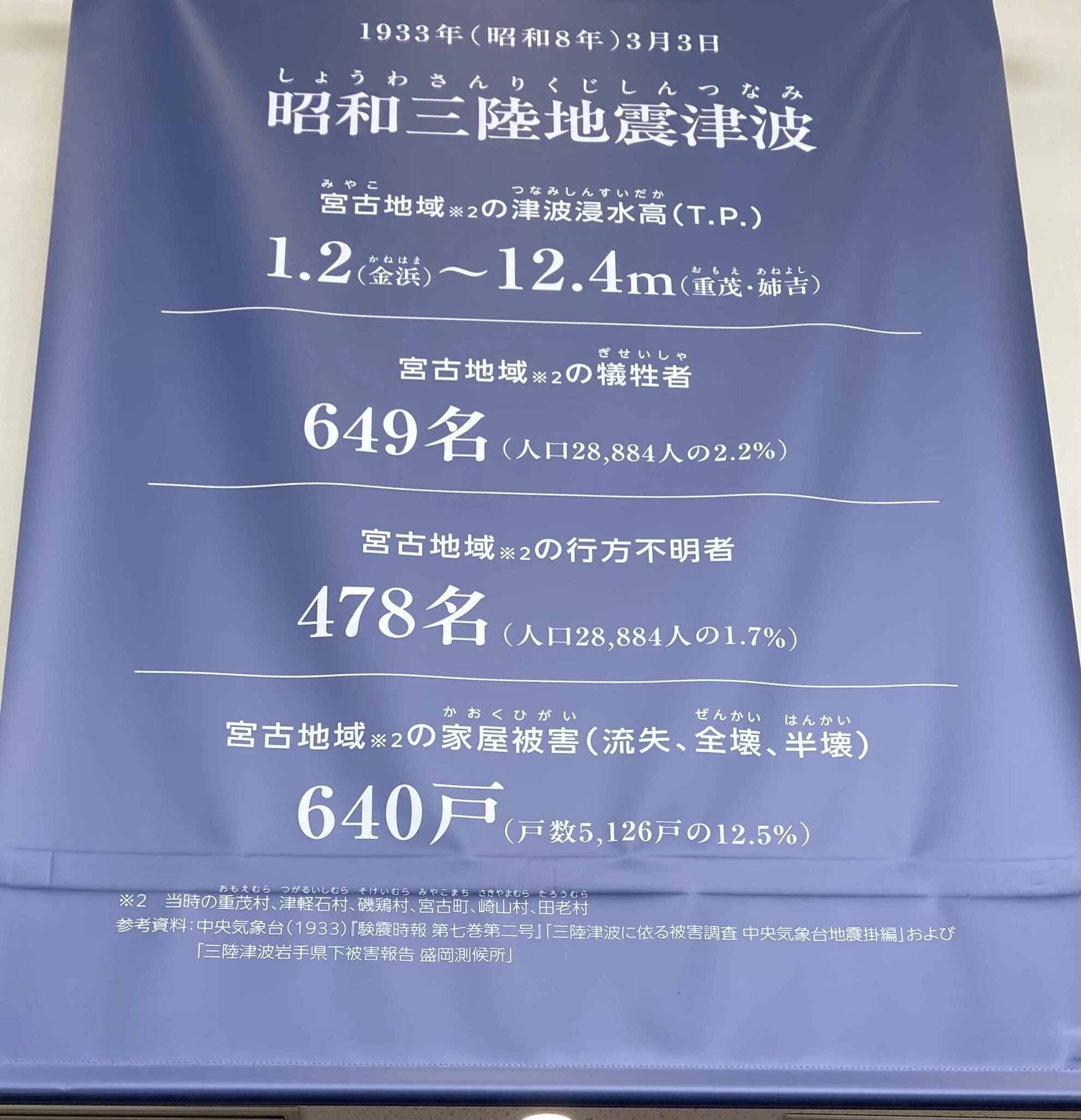

What struck me most were three large, banner-like panels displayed at the entrance.

It seems the “tsunami tendenko” teaching was heeded across Miyako as well. Although the maximum inundation height during the Great East Japan Earthquake was nearly 30 meters and 4,449 homes were damaged—the worst on record—the number of fatalities was lower than in the 1896 and 1933 tsunamis.

Having hurried through, I apologized to the staff for the rush, promised I’d come again, and headed back to the station.

Wait… where was the station? Time was running out.

The sign read “Sanriku Railway Shin-Taro Station.”

Thank goodness—I hadn’t gone the wrong way. I should’ve turned around once when I first got off. Here, the city offices, chamber of commerce, bank, and the station building are all clustered together.

If you take the elevator (or stairs) to the third floor of the General Affairs Office, there’s a passage from the building straight onto the Taro Station platform. Chairs are lined up along the corridor from the elevator to the platform, making a kind of waiting room. With seven or eight minutes left before the train, I sat down—better than standing on the platform with no shade. An elderly woman came by.

We exchanged greetings, and she switched on a nearby fan.

“It’s hot, isn’t it? Here, when you’re waiting for the train, you turn the fan on yourself—and when you board, you switch it off yourself.”

I thought she must live nearby; she could tell at a glance I wasn’t local. There was another fan next to me, so I pressed the button to turn it on, too.

I noticed a poster for the Disaster Archives and Remembrance Museum and told her I’d been traveling all through Tohoku and had just visited the museum.

“I live just a short walk from here,” she said gently. “I only went there myself quite recently.”

Something in her tone made me feel there was a line I shouldn’t cross.

“The water came very high around here, didn’t it? I didn’t experience the tsunami myself, so I can’t truly imagine it—but after walking around, I can see that something terrible happened.”

“The tsunami was truly terrifying,” she replied, pointing toward the hill. “We all went up there and watched the sea.”

“It was terrible… but somehow, I’ve forgotten now.”

Her words struck me in the chest. I couldn’t say anything.

When the time came, we both switched off the fans beside us and stepped out onto the platform.

“The Sanriku Railway is so cute—I’ve become a real fan,” I said.

“It’s small and charming, isn’t it? Please take lots of pictures,” she answered.

With that, I left Taro and began my journey home.

Her words stayed with me. She had seen that tsunami; the town where she had lived her whole life had been left in ruins; surely she had not come through without losing things she loved. And yet she had kept on living here—and would go on living here.

I wondered how much lay behind the simple phrase, “I’ve forgotten.”

And I found myself hoping that someday I, too, might smile quietly and say that I’ve forgotten—that someday I might become someone who can fold away pain and sorrow without placing them on anyone else, and live with a calm heart.

It was a wonderful journey, full of rare experiences. When I look back on it, there is something I cannot put into words—yet it continues to reverberate deep within me.

I promised the salmon resting peacefully on the grass that I would come back to see it again.

And I intend to return to the sea of Tohoku.